Martial Ethics: The Pillars of Traditional Martial Arts’ Endurance

Written By

Aryanmehr

Date Published

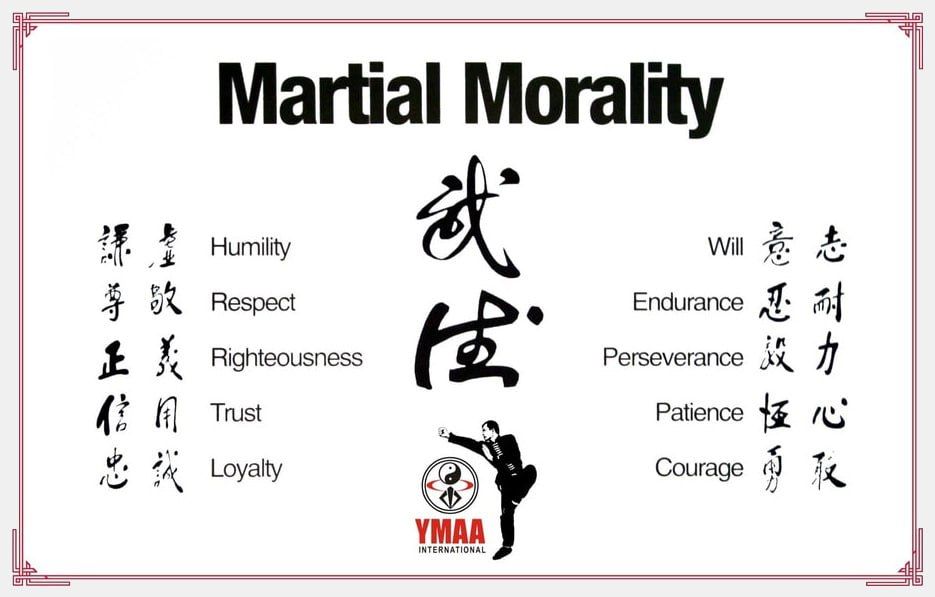

In the authentic schools of martial arts, techniques and physical skills are only part of the path. The true foundation of martial arts lies in ethics and character—the “Wu De” (武德 – Martial Morality), which in Chinese, Japanese, Iranian, and many other civilizations is recognized as the bridge between power and responsibility. Great masters have always emphasized: “One who relies only on the strength of the arm shortens the life of their art; but one who centers on morality will pass on their legacy for generations.”

In the YMAA tradition, there are ten fundamental principles for cultivating both martial skill and personal character, which we review here with explanations and historical examples:

1. Humility (謙)

Humility means accepting that there is always room to grow. Chinese masters would say: “A full cup can hold nothing more.” In Iranian history, Rostam of the Shahnameh, despite his great strength, bowed before wise elders to benefit from their experience. In Tai Chi Chuan, humility is the foundation of proper learning; one who believes they are already complete stops moving forward.

2. Respect (敬)

Respect is the bond that connects generations—respect for the teacher, the training partner, the opponent, and even the tools of practice. Before battle, the samurai would bow to their rival, showing that for them, the fight was not merely about victory but a test of honor. At YMAA, respect includes observing the etiquette of the training hall, caring for uniforms and weapons, and maintaining dignified behavior inside and outside the class.

3. Righteousness (正)

Righteousness means choosing the right path even when the easiest path is the wrong one. Yue Fei, the loyal Chinese general, became a symbol of righteousness in Chinese culture for his commitment to principles and defense of his homeland. In martial arts, righteousness means using skills to defend what is right, never for oppression or selfish gain.

4. Trust (信)

Trust is the capital shared between teacher and student, and between fellow practitioners. In the old martial schools, a master would share their complete knowledge only with a student who had proven worthy of trust. This principle is just as true today; a team without mutual trust will lack coordination in both training and the field.

5. Loyalty (忠)

Loyalty means steadfastness in commitments and honoring the path and the school. In Chinese history, the disciples of the Chen family in Tai Chi Chuan continued to preserve the names of their masters even after dispersing. In Iran, pahlevans of the traditional Zurkhaneh have always remained loyal to their morad (master) and customs. Loyalty at YMAA means upholding the authentic lineage of Dr. Yang, Jwing-Ming, and transmitting the teachings without alteration.

6. Will (志)

Will is the driving force behind all progress. Morihei Ueshiba (founder of Aikido), despite the defeats and hardships of wartime, never abandoned his path, and his art is now practiced worldwide. In Tai Chi Chuan, will means showing up for training consistently, even on days when motivation is low.

7. Endurance (耐力)

Endurance is the ability to continue under difficult conditions. The Shaolin monks endured years of rigorous, exhausting training to unify body, mind, and spirit. In Iranian history, Gholamreza Takhti, the legendary wrestler, persevered despite physical and emotional challenges.

8. Perseverance (毅)

Perseverance means returning to the path after every failure. The old masters would say: “Practice one technique a thousand times to truly own it.” In Tai Chi Chuan, even a simple move such as “Embrace Tiger, Return to Mountain” can take years to become deeply ingrained in body and mind.

9. Patience (恆)

Patience is the art of moving slowly and steadily. Daoist philosophy says: “Water, with patience, wears away the hardest stone.” Many great masters trained in seclusion for decades before reaching the stage of Wu Wei (natural effortless action).

10. Courage (勇)

Courage is the conscious facing of fear. This principle appears throughout history, from wartime generals to sports champions. In martial arts, courage is not only in the fighting arena but also in everyday life: standing for what is right, choosing the difficult path, and giving up comfort and complacency.

Conclusion

These ten principles are not merely a list of words; they are a way of life—extending beyond the training hall into home, work, and human relationships. Martial arts without morality is like a sword without a sheath: sharp, but dangerous.

At YMAA, we believe that every student must cultivate these values in heart and action alongside their technical progress, so they may become not only skilled martial artists but also more complete human beings.